01.05.24

Experiences and hopes of a primary school teacher: Dual language education from Wales to the Middle East

By Ellie Thomas

Image above: Ellie in the traditional Welsh dress with her class

The origins of the word “Wales” comes from the Anglo-Saxon word wēalas, meaning “foreigners” or “outsiders”. It is tied to the image of the unwelcoming and angry Celt, whose ancestors until this day share the same hostility and suspicion towards anyone who isn’t from this land. Our word for Wales is “Cymru” and it descends from the Brythonic word combrogi, meaning “friends” or a “fellow-countrymen“.

And as a proud Cymraes, I find this a much more fitting name for my country. Cymru is a beautiful and inviting land, with its own rich history, customs, culture and song that any Cymro or Cymraes would be happy to share with you. But perhaps what we are the proudest of is our language.

There is a saying in Welsh, “Cenedl heb iaith, cenedl heb galon”– “A nation without a language is a nation without a heart”– and the heart of our national culture continues to be the Welsh language. However, this is an issue that the Welsh people have fought hard for. Over the past 100 years, the efforts of Welsh politicians, activists and communities have ensured the continuation of our language. The Industrial Revolution sparked the decline of the Welsh language, with mass migration of inhabitants from England moving into Wales and English becoming the official language in the workplace. This was followed by the tragic loss of welsh speaking men on the battlefield of Europe – in the First and Second World War. Amidst this, Plaid Cymru was founded in 1925, a political party with the principal aims to promote the Welsh language and culture. In the following decades, language campaigns led to the first Welsh language radio station, BBC Cymru, in 1977, and first Welsh language TV channel, S4C, in 1982. Within education, Welsh became introduced as a ‘core’ and ‘compulsory’ subject in 1988 and there was a growth in Welsh-medium schools. In 1993, the UK Parliament passed the Welsh Language Act, which gave the language official standing as an equal language to English. Finally, in 1999, the establishment of the Senedd Cymraeg – Welsh government – gave Welsh elected members control over agriculture, health care, education, transport and language within the country. And after a referendum in 2011, the Welsh Assembly was given the authority to enact laws directly, without first consulting Westminster.

I grew up on the island of Anglesey – known as ‘Ynys Môn’ or ‘Môn, Mam Cymru meaning “Môn, Mother of Wales”. It is in the North of Wales, which is considered to be ‘Welsh Wales’, as the Welsh language can be heard in every school, shop and park. Over half of the island’s population speak Welsh, with some communities boasting that over 70% are using the language. Anglesey is admired for its beautiful coastline, vast green countryside and sleepy villages. It has gained notability for the long Welsh names given to these villages – in particular, Llanfairpwllgwyngyllgogerychwyrndrobwllllantysiliogogogoch.

Locals feel strongly about maintaining Welsh names in this area, and a recent petition in 2023 has called for the island of Anglesey to be referred to by its Welsh name only. Although this petition was rejected, it gathered support from over 2,000 signatures, mirroring a national movement to take ownership of the land and return places to only Welsh names – recently, Snowndon and Snowdonia has become known exclusively as Eryri and Yr Wyddfa.

Within my own family, my father is Welsh and my mother is English – making the language actually my ‘father’ tongue. My mother made a conscious effort to learn Welsh and embraced her husband’s country and language. With our parents, myself and my sister would speak our own kind of Wenglish – freely talking between the two languages. A further influence came from another adult living in our home: my Taid (Welsh for Grandfather). Having grown up in a nearby slate quarrying community, my Taid had spoken only Welsh until he was 14 when he was taught English in school. He remained an advocate for his beloved language for the rest of his life – most remarkably as an actor on Welsh television and radio. With his grandchildren, he would talk, read, sing and most importantly, correct us in Welsh. I will always accredit him as being my greatest teacher in understanding the Welsh language and culture. By the time I was ready for school, I had a strong understanding of who I was and the two languages and cultures I came from.

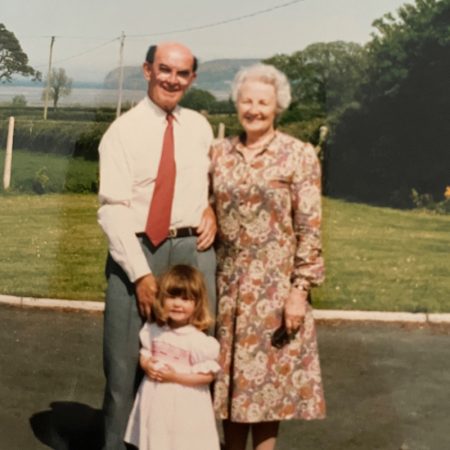

Image above: Ellie with her Taid (grandfather) and his sister – Anti Jên.

Almost all of the primary schools in my area are Welsh medium – and mine was no exception. During each school day, I was expected to speak Welsh to my teachers – and even with my friends on the playground. In the first years of education all my lessons were held solely in Welsh, and it was only until I turned seven that English would be incorporated. My favourite part of school was history, specifically Welsh history. From the legends of the Mabinogion to the rise of the Tudur family to the Great Strike at the Penrhyn Quarry, these lessons only intensified my strong sense of Welsh identify. This interest in local – or as I saw it, “my” – history followed me to secondary school. Now in a bilingual school, I took my GCSE and A-Level history classes between two teachers, one taught in Welsh and the other in English. This love of the subject led me to gain a place to study History in a respected University in England.

The Welsh word ‘hiraeth’ has no direct English translation, but it is synonymous with the feeling of being homesick, especially in the context of Wales and Welsh culture. While I was well-travelled by the age of 18, I had only ever lived and been educated in Wales. Hence during the first year of university, I experienced the unnerving feelings of hiraeth – in missing my country with its familiar language and customs – to disorientation – in adapting to a predominantly English environment and people. With grudging acceptance, I became accustom to no longer recognising my familiar ‘father’ tongue around me in an educational setting. Instead, I attended lecturers in English, I spoke to my Professors and peers in English, I read and wrote papers in English, I presented my work in English and ultimately, I pursued my academic life in English.

Over the last ten years, I have worked and lived in England and the Middle East. I also continued my education – completing an MA and now undertaking a PhD – studying in English. And while I have not lost my identity as being a proud Cymraes, I still hold onto the guilt that I may never be able to read and write in Welsh as fluently as I did when I left school. Since I had stopped studying in the language, I felt myself losing academic competence in it. I recall an early meeting with one of my professors with whom I expressed my struggles about no longer learning through Welsh. Although he was sympathetic to my issue, it was made clear that English was the main language in this institution and I should attend writing skills sessions or find a tutor if I was struggling with this. He had misunderstood that I did not want to improve my English, but rather maintain my Welsh. Our universities hold such an emphasis on having the required level of English to attend, that many fail to embrace all the incredible languages and cultures that exist in their institutions. To support students like myself, it would beneficial to allow us to celebrate our language and home. Also, provide them with opportunities to use their unique language skills or share significant parts of their history or culture. In recent years, I have been pleased to there have been some exciting developments in this area. The rise in Welsh societies across English universities has offered undergraduates from Wales a place to speak, share ideas and discuss work in their own language. An excellent example is the UCL’s Welsh Society, which organises Welsh lessons, conversational sessions and history talks.

Nonetheless, this has been slow process and while the Welsh language may be getting some recognition, there will be other bilingual learners speaking minority languages who are feeling exactly how I did. My message to them is this: your home language is your greatest asset. An outdated formal education system will have you believe that we should all be monologists English speakers but this is actually limits you in the multilingual real world we live in. My Welsh language has given me so many exciting opportunities and allowed me to meet interesting people – it was actually what sparked a conversation between myself and my PhD supervisor, Dr Dina Mehmedbegovic-Smith! Dina, who works as a consultant on bilingualism with GEMS schools in Dubai, delivered several professional development sessions in my school in which she promoted development of bilingual academic proficiency through her approach Healthy Linguistic Diet. Dina’s sessions have inspired me to use my background and experiences in my professional role and led to starting my doctorate, with a focus on dual language learners and maintaining one’s home language and culture.

Ellie and Dina in GEMS Al Barsha School, Dubai

My role as an EAL teacher has brought me to work in a National School in Dubai, where I find the local population of the United Arab Emirates in a similar position to the Welsh. With the rapid globalization of the country and dominance of the English language, Emirati families have raised concerns that their children are losing their language and culture.

I believe that the first years of a child’s life are crucial in developing dual language skills and instilling understanding of their culture. Hence, my research interests specifically lie in understanding the role of adults in guiding and supporting children in early years education to learn two languages simultaneously, both at school and home. Much like my own education, my research will be conducted in a dual language school and I am interested to speak to parents and teachers to examine the impact this is having on students and their proficiency in two languages. I hope that my research can raise awareness to dual language education and encourage parents and teachers to embrace multilingual practices in their homes and schools. But most importantly, I wish to empower young bilingual children to strengthen their voice and identity in their home language, while learning an additional language.