10.04.18

What language should migrants speak to their children? A survey among Polish migrants in the UK

By Dorota Peszkowska

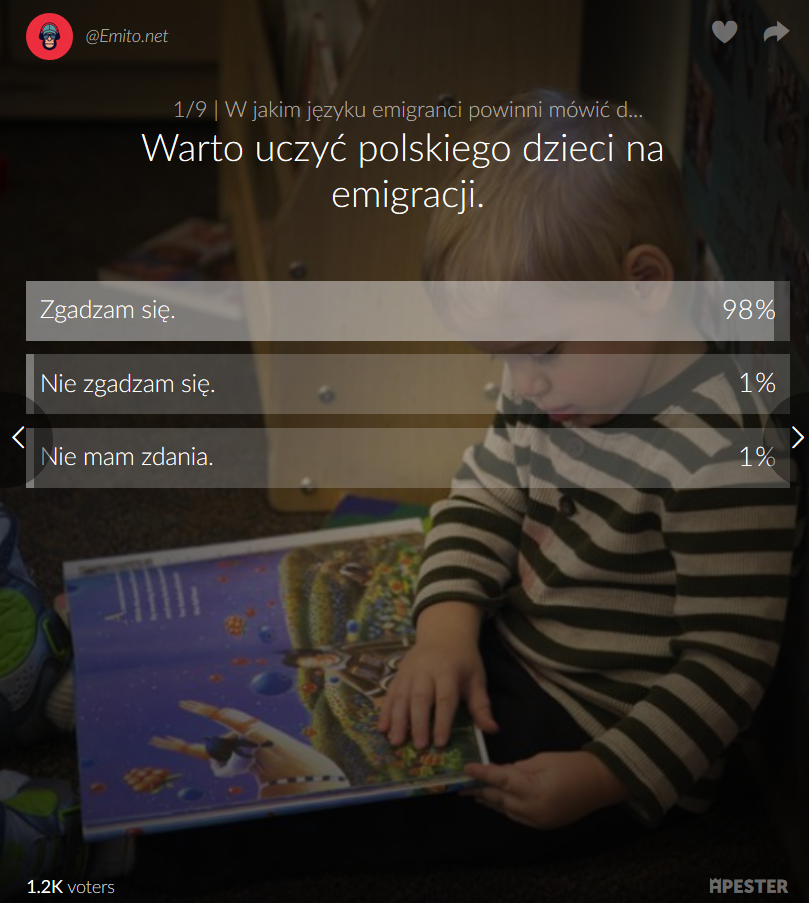

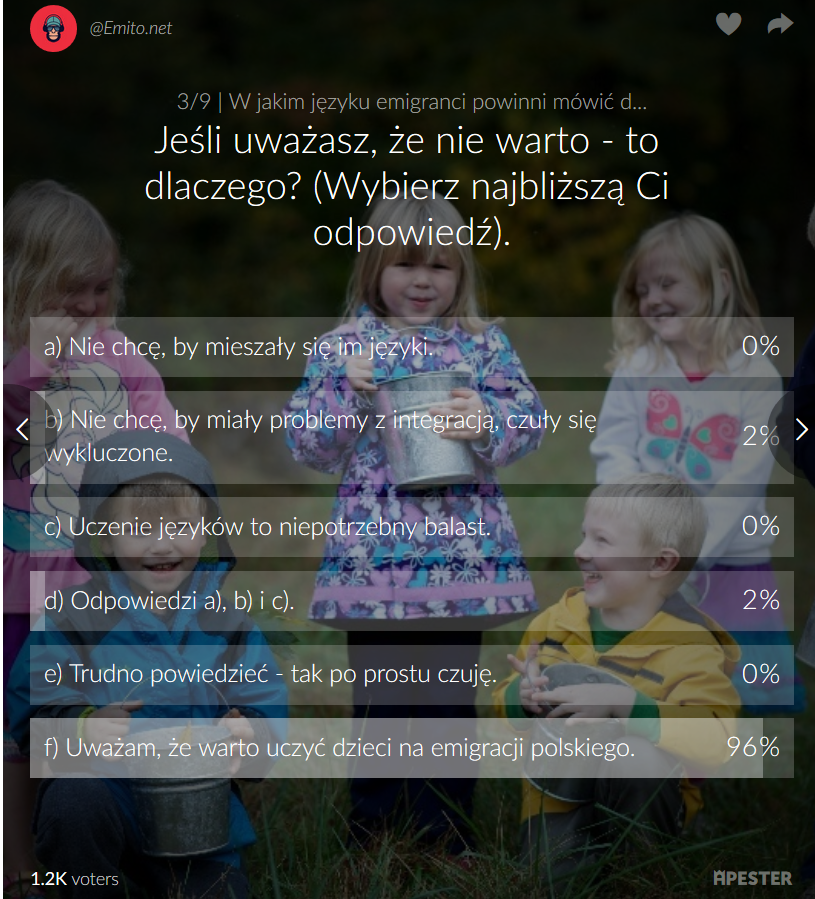

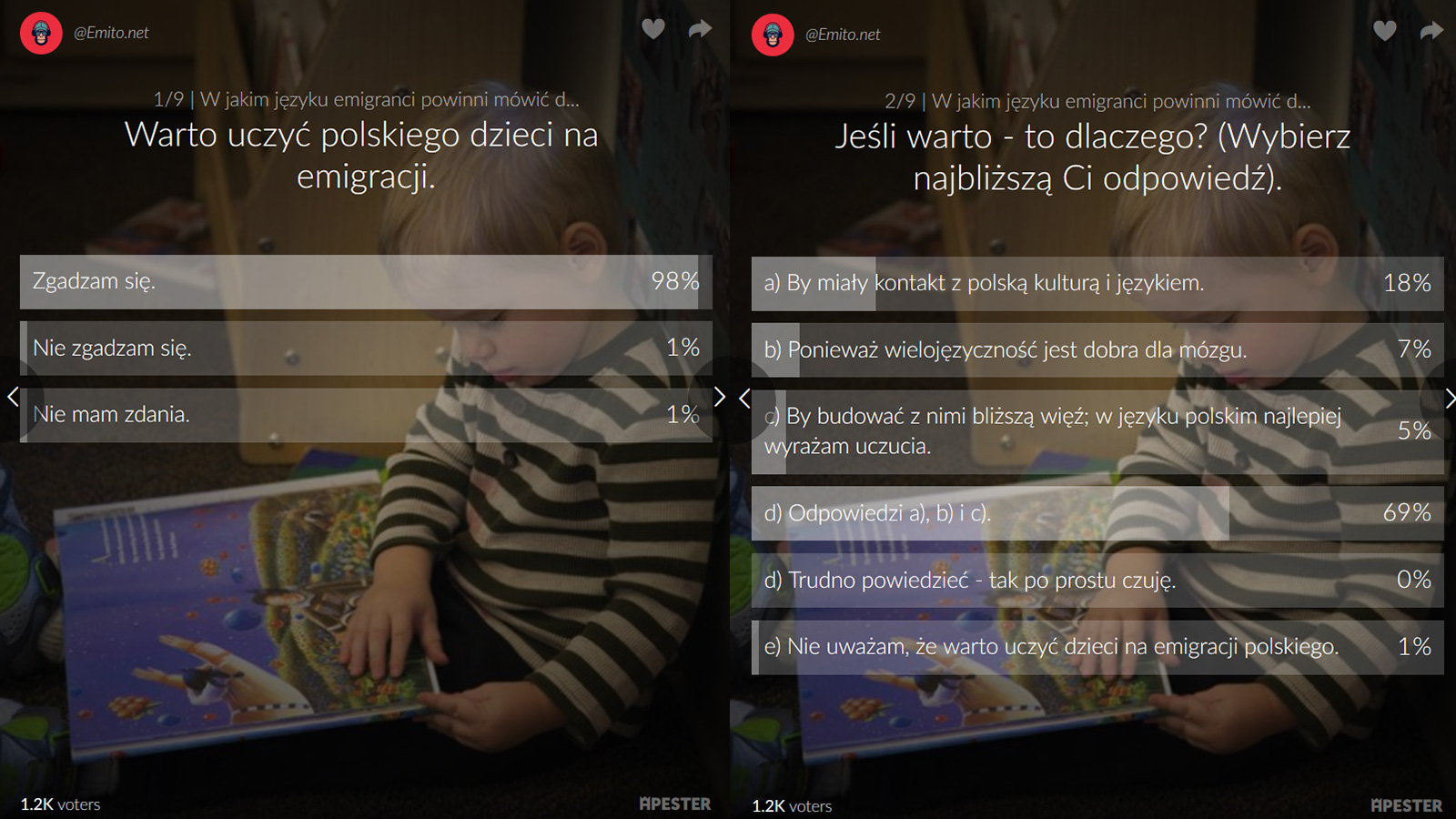

As many as 96% of Polish migrants in the UK agree that it is good to teach their children their mother tongue, according to a survey of 1,200 Polish expats. The remaining 4% who don’t share this view worry mainly that their offspring would not integrate well in the society and feel excluded by their peers; the fear that the children will confuse both languages and the idea that additional languages are a burden for them are less frequent (for more details, see the screenshots below).

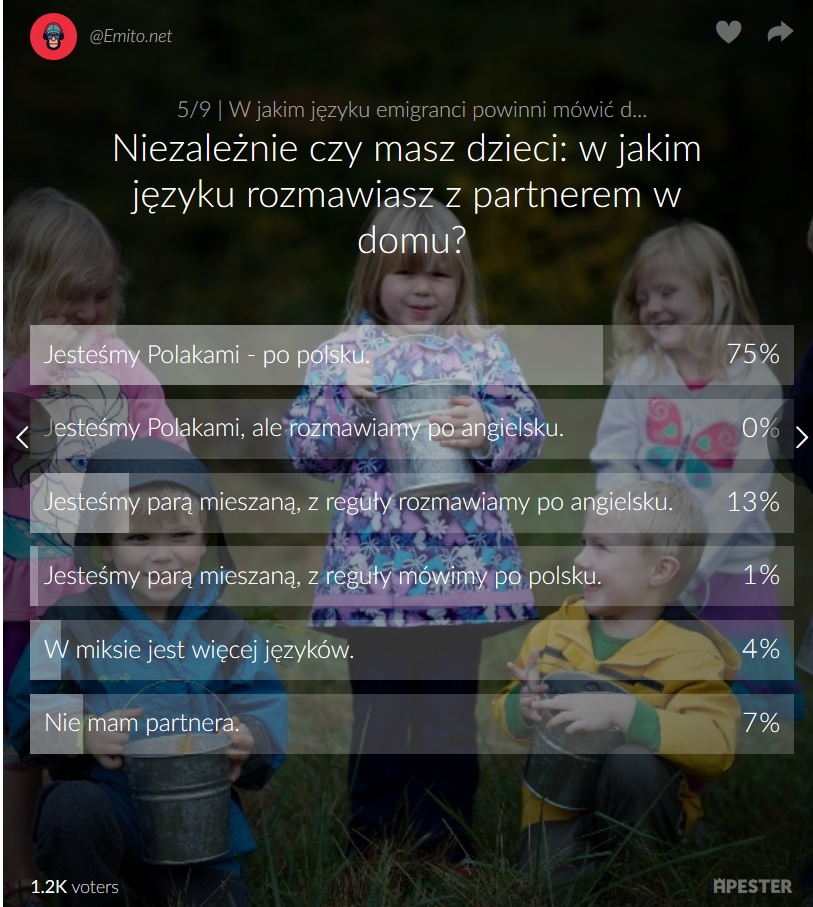

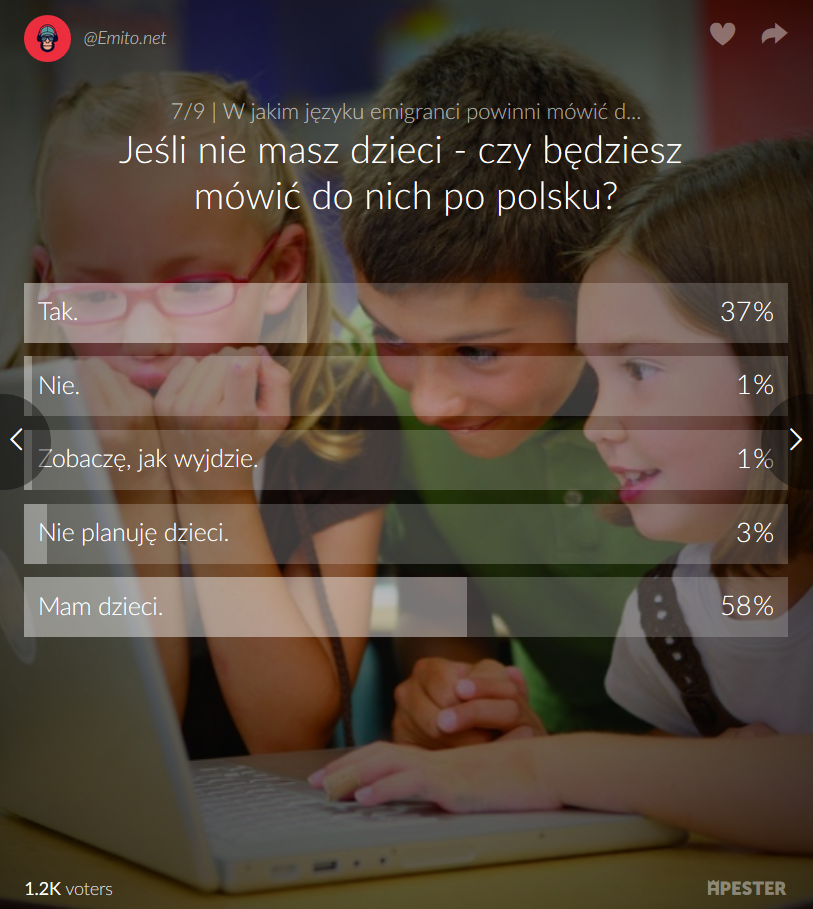

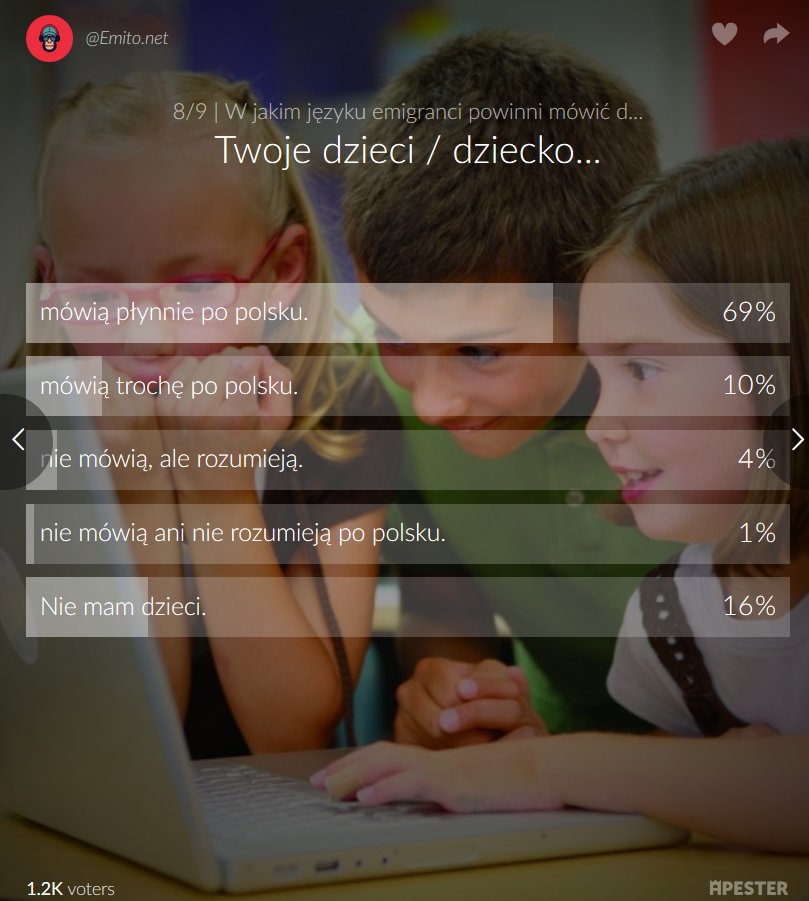

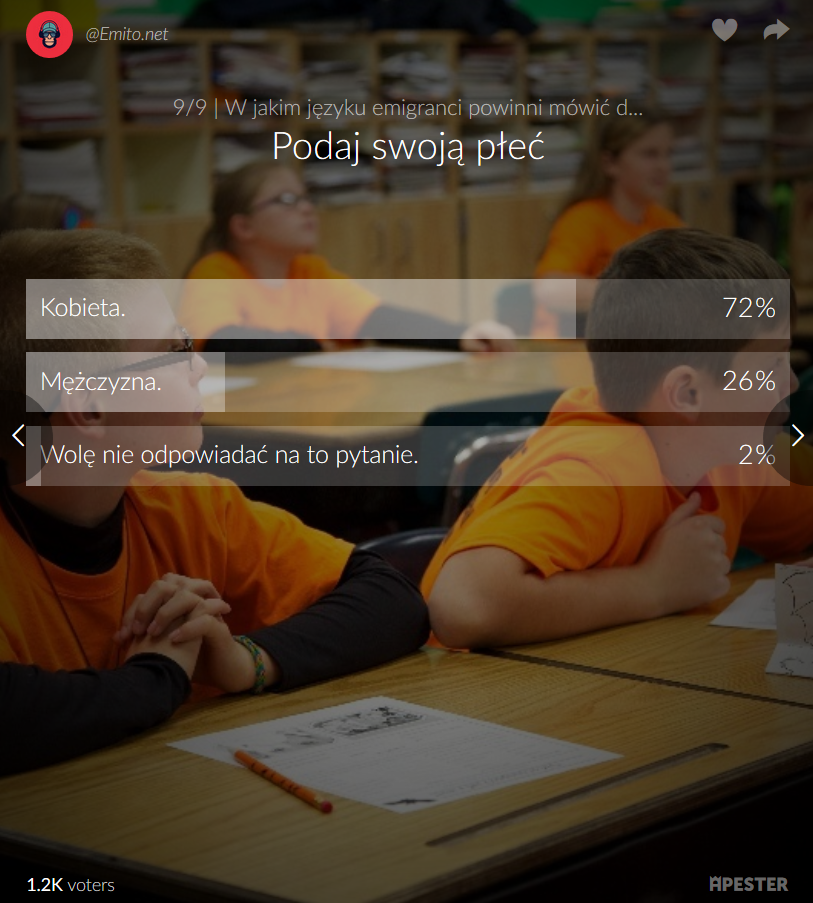

The survey was run in Polish on Emito.net – a website for the UK’s Polish Community, visited by over 500,000 Polish expats in the UK every month. The survey ran for 3 weeks; 72% of the participants were women and 84% had children. Among those respondents who have children, 64% speak with them mainly in Polish and only 2% in English. In 8% of cases, the parents speak to their children in Polish and children answer in English. Remarkably, 25% reported that the language they speak with their children depends on the situation, so in different contexts they might be using either Polish or English.

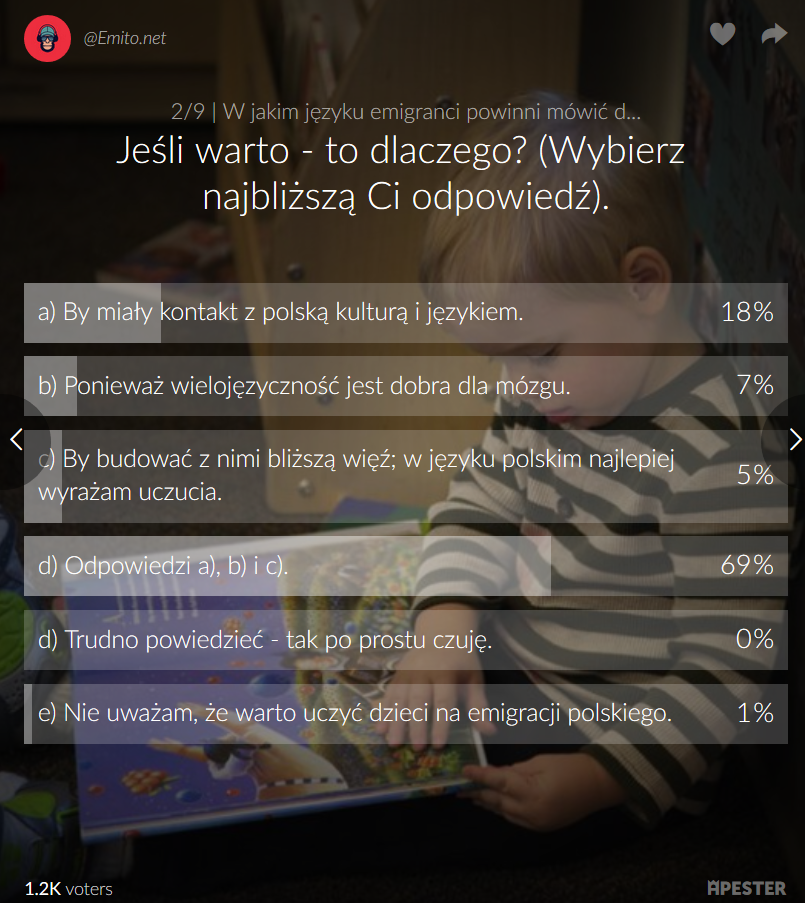

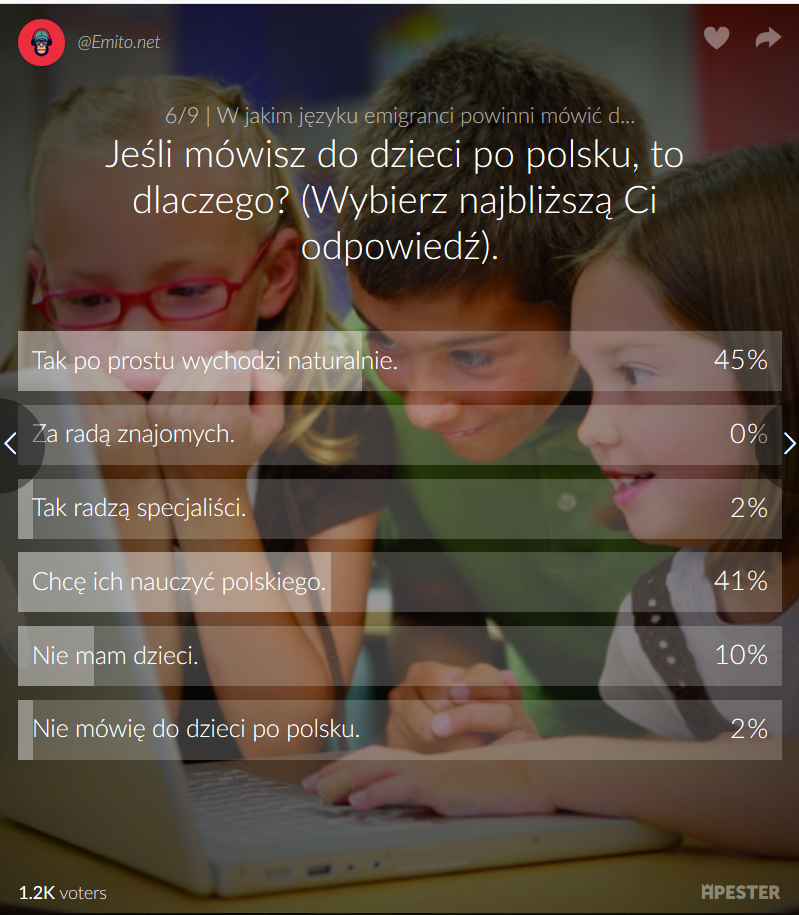

Among those parents who speak Polish to their children, roughly half (50%) do it because “it feels most natural”, while others (46%) are consciously trying to teach their children Polish. Parents’ wish that their children learn Polish is influenced by several factors: to “keep them in touch with Polish language and culture” (18%), because “speaking different languages is good for the brain” (7%), to “communicate in a language that enabled them to express their feelings best” (5%) and a combination of all three (69%).

Such a unanimously positive response to multilingualism and teaching the so-called “heritage” language of a migrant community may seem quite surprising. However, it reflects the reality of life for the biggest migrant group in the UK. With a diaspora over 1 million strong, the UK’s Poles are able to have a thriving social life in Polish, using English mainly at work. A stark example of this is the fact that a Polish-only website, targeted primarily at the Polish community in Scotland, was able to attract over one thousand participants for a survey in a matter of weeks.

The replies can also be explained otherwise. It should perhaps be rather obvious that a user of a Polish-language website in the UK, who searches news in Polish rather than in English, would also be eager to speak Polish to their children or to speak exclusively Polish at home. Furthermore, those who chose to participate in the survey and speak Polish at home, might have been inclined to justify their behaviour and look for as many positive outcomes of this practice as possible, therefore ignoring their fears about raising children multilingually. Conversely, it is possible that many people who do not use Polish with their children chose not to fill in the survey due to feelings of guilt – this is speculation based on personal exchanges with some of the people invited to participate.

Nonetheless, the survey results do show a huge appetite for languages other than English in the UK. It is a stark reminder that many migrants – who now constitute over 13% of British society – live in a multilingual, not monolingual society. This last point is particularly true for migrant children, who often use their parents’ mother-tongue at home and English at school. Additionally, for many participants the language they use, even with their own children, depends on the context! So for children, the two languages may constitute equally important part of their identities (which seems to be both parents’ hope when teaching them their mother-tongue, and the strongest deterrent from doing so).

Of course, this multilingual landscape of Polish migrants is painted here with a very broad brush. It does not explain which language migrants and their children use most of the day, how social contexts determine the languages chosen, and how children feel about their multilingualism. It does however prove that a great number of migrants in this country feel strongly about multilingualism, as reflected by the high participation, and the heated discussions that ensued in the comment section below the survey (see the attachments below). Hopefully, this will be reflected in the future debate on this topic.