04.07.18

Languages and penalties

By Thomas H Bak

When I was speaking last June in Entebbe, Uganda, at the Congress of the Society of African Neuroscientists about the positive cognitive effects of language learning in childhood as well as in adulthood (indeed, including old age), the first question I got was: “Sir, I am from Ghana, and in Ghana we usually speak 3-4 languages. Is it better to speak 5, 6, or 7?” A similar question could easily arise in India and in many other places across the world, in which multilingualism is a rule rather than an exception.

In Britain, in contrast, I tend to get the opposite question: “But is it possible to learn a new language after childhood?” Often followed by the assertion, that being English (or having English as one’s mother tongue) somehow prevents you from ever learning another language. So it’s better not even to attempt.

Until yesterday, I found it difficult to answer this question. Of course I could say that there is no evidence for that, cite examples of many English people successfully learning different languages, explain how negative expectations can lower performance. Still, my feeling was that my audience was not terribly convinced.

But then, until yesterday, there was also a wide-spread belief that being English somehow prevents you magically from being able to take penalties. I am sure that when the extra time ended in a draw most people in England felt: that’s it, yet again. But it was not to be. Whatever might happen in this so beautifully unpredictable World Cup, no-one will ever say again that English are doomed to lose every penalty shoot-out they end up entering. Yes, they might loose the next one, things never go well every time (as Germany, Argentine and Spain have already experienced), but the fatalistic spell is broken.

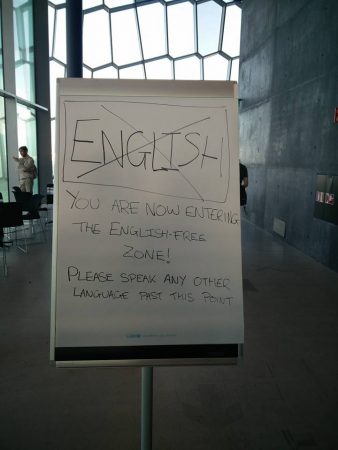

The English-free zone, introduced by English speakers at the Polyglot Conference in Reykjavik, October 2017, to enable them to practice all other languages they know or want to learn.

What it takes for the stereotype of English not being able to learn new languages is only one thing: not to believe in it. And then convince other people not to believe in it, including speakers of other languages. Ironically, one of the real difficulties English-speakers are faced when learning a foreign language is the fact that everybody switches to English as soon as they are around; partly due to the wish to practice English, partly out of misplaced politeness. At the Polyglot Conference in Reykjavik last year (a wonderful yearly event organised by language enthusiasts from all over the world), English-speakers developed a great idea: an English-free zone, where they could practice their languages, without others falling back into speaking English to them. The idea was very popular with everybody and it is likely that it will be implemented again at the next Polyglot Conference in Ljubljana in October 2018:

https://www.facebook.com/groups/polyglotconference/.

The example of Gareth Southgate, breaking a 22-year old bad spell is certainly inspiring, not only for football fans. But there is one more reason why are gave this blog the title “Languages and penalties”. Many people whose only experience of language learning was at school might indeed associate language with penalties: penalties for forgetting the vocabulary, penalties for mispronouncing the words, penalties for using wrong grammatical forms. Little fun, many penalties…

In the morbidly competitive society we live in we are trained since earliest childhood to meet targets, tick the boxes and outperform others. There is nothing wrong about being ambitious, trying to do things as well as possible and achieve the highest levels of accomplishment. But paradoxically, an obsession with success, perfection and competition may be one of the main sources of failure; certainly so in language learning.

A good example that language learning can be about fun rather than penalties is offered by a new pioneering Scottish social enterprise Lingo Flamingo: http://www.lingoflamingo.co.uk/. Lingo Flamingo offers courses to older people and even to patients diagnosed with dementia. Their motto is that it is never too late to start learning a language and that every person can benefit from it: cognitively, psychologically, socially. The feedback I have experienced from people who did their courses has been tremendous: people perceived them as “challenging” but also as “fun”, “rewarding” and “energising”. And they were stunned how much they have learned. Dina Mehmedbegovic and myself follow a similar path with our concept of “Healthy Linguistic Diet”, as presented in this website: a multilingual world in which people are exposed to different languages and learn them to various degrees of proficiency. The perfect, native like proficiency which many fear failing to achieve especially when it comes to accents, is replaced by the liberating ideal of an effective communicator who draws on the full variety of their linguistic and cultural knowledge and experiences to produce effective communication.

So what I would like to say to all my English-speaking friends, when they might ask themselves: can we learn another language is that there can only be one answer to this question: Yes, we can!

- You can hear more about Thomas H Bak’s ideas on language learning, education and society in his shows at the Edinburgh Fringe on 13 and 16 of August 2018: https://www.outstandingtickets.com/show/515/ditch_the_classroom;_speak_in_tongues_(cabaret_of_dangerous_ideas_2018)