16.04.18

Postdoc (and some rather personal) reflections on multilingualism in Osijek

By Klara Bilić Meštrić

Osijek (Croatian pronunciation: [ôsijeːk]) is the fourth largest city in Croatia with a population of 108,048 in 2011. It is the largest city and the economic and cultural centre of the eastern Croatian region of Slavonia, as well as the administrative centre of Osijek-Baranja County. Osijek is located on the right bank of the river Drava, 25 kilometres (16 mi) upstream of its confluence with the Danube (…).

The name was given to the city due to its position on elevated ground which prevented the city being flooded by the local swamp waters. Its name Osijek comes from the Croatian word “oseka” which means “ebb tide“. Due to its history within the Habsburg Monarchy and (…) in the Ottoman Empire, as well as the presence of German and Hungarian minorities throughout its history, Osijek has (or had) its names in other languages, notably Hungarian: Eszék, German: Esseg or Essegg, Turkish: Ösek, Latin: Essec. It is also spelled Esgek. Its ancient name was Mursa and is supposed to come from the Proto-Indo-European word *móri (sea, marshland). (Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia)

The Wikipedia quote notwithstanding, I’ll start this post with personal recollections. I remember growing up in Retfala, what used to be a Hungarian part of Osijek, and feeling a kind of quiet admiration for people who spoke this language. And, to be honest, it’s never been just about the language, it’s always been more about the people. What does it feel to be them and grow up in that language and culture? Can we ever fully comprehend each other if we have different cultural and linguistic background? And the variations – can you ever fully master some other language and the background knowledge it carries? As a child there were so many unarticulated questions which drew me to foreign cultures, and in not purely affective way, they certainly still do. My grandparents and my parents took me everywhere across what was then Yugoslavia and I was fascinated with various vernaculars that all fell under a single common denominator. And I remember that even back then there were taboos – covert rules on which words you could say where and brief explanations just to satisfy your curiosity (never underestimate the implicit knowledge of a child). Language gave it all away, before it was fully there with the war and everything.

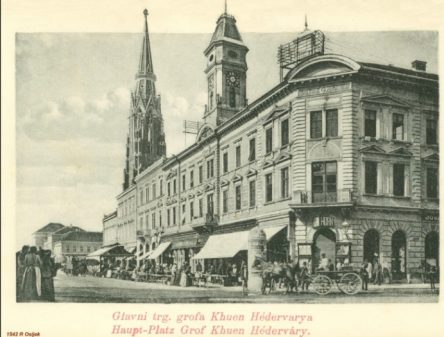

City and university library Osijek, Archive

One of the most fascinating visits did not take place very far away. My grandpa took me to the countryside just a bit out of Osijek on his land which he gave to a couple of Gipsy families. I remember sitting in their tents and playing with women and children. They brushed my hair and were examining me closely, they gave me some necklaces and earrings, trying to please me. I wasn’t aware back then, but now I think of all this as a huge privilege – having it natural to sit in a Gipsy tent, visit those other parts of the country and listen to other idioms. Back then, the others of Yugoslavia either came to our house or I was taken to them, and, after all, it wasn’t only my family’s openness which made me aware that I was growing in a multilingual world, it was the whole town. This world will become an object of my inquiry. As with the Gypsy family or the Hungarian city heritage, one didn’t need to go far to encounter it. Beneath the unifying linguistic surface, my own town was hiding fascinating multilingual and multicultural richness.

City and university library Osijek, Archive

This richness was formally explored through the LUCIDE project in which the Josip Juraj Strossmayer University of Osijek (Faculty of Education) participated from 2011 to 2014. LUCIDE stands for Languages in Urban Communities – Integration and Diversity for Europe and it was a network of Twelve European cities and two overseas universities (the University of Melbourne and the University of Ottawa) that took part in the project whose aim was to explore multilingual practices and language policies in urban centres across Europe and wider, in order to develop guidelines on fostering multilingualism. Research was primarily based on interviews with relevant stakeholders – language policy makers and their users in five social spheres; economic, public, urban, educational and individual. The Osijek study, which I conducted with Professor Ljiljana Kolenić from the Faculty of Social Sciences and Humanities, showed that multilingualism was promoted at official levels in the form of different laws and regulations (especially with the Law on education in the language and script of national minorities), but that the city was lacking in real initiatives, at least with regard to minority languages.

Modern Osijek: Photographer Ivan Rajs

The City and University Library in Osijek turned out to be an exception to this trend, especially through the passionate work of Ms. Suzana Biglbauer and Mr. Siniša Petković. With the Festival of Languages, an annual week-long celebration of multilingual practices comprising workshops, lectures, and the final manifestation – the Celebration of Language, they have been marking the International Language Day for years now. The whole event in the city and its immediate surroundings is a rare chance to hear the minorities from Osijek and Slavonia and Baranja regions and to listen to the stories and see performances in Hungarian, Serbian, Roman (Bayash), Russian, Slovak, Ruthenian and other minority languages.

The topic of my PhD thesis was also connected with the project. Under the careful mentorship of Professor Dina Mehmedbegović from the London Institute of Education, extending the data from the project, I wrote a doctoral thesis with the focus on pupils from Osijek schools who nurture their languages in one of the minority education models. Research with children and young people has revealed that they perceive their language as personal capital, but not as the capital of the whole community. The research has also shown that language is still a contested ground as the society has not fully recovered since the Homeland War in the 1990s. The current and, to some degree, even dramatic emigration trend only confirms the conclusions of this level of research.

Although the official data, at least that from the last Census, state that almost 20 different languages are spoken in Osijek (as first languages), the data could be perceived as a relic of the past as they do not mirror actual practices. According to the 2011 Census, only slightly over 80,000 inhabitants lived in Osijek back then, while the numbers circulated around 100,000 at the dawn of war in the 1991 Census. Many are anxious about the 2021 Census as a further (dramatic) shrinkage is under way.

The history of the city in the twentieth century could be analyzed as a history of gradual, and at times even dramatic loss – in both linguistic and human terms (as if one without the other could actually exist). Grammars, dictionaries and numerous books and newspapers that were published in several languages are merely a monument to the former multilingualism, the drying out of a town in which, at the beginning of the century, alongside Croatian one could hear German, Hungarian, Serbian… German was spoken in Downtown and Uppertown, while Retfala, then the suburbs, was inhabited by Hungarians. However, a majority of ordinary citizens spoke Essekerisch or Esseker German, an autochthonous German dialect mixed with Croatian, Hungarian, Serbian and Yiddish, spoken exclusively in Osijek.

Though the speech almost vanished after World War II, as it was symbolically too closely tied to the enemy, it is still present in the lexicon of a few remaining Essekers, but also of people born in post-war Osijek and their descendants. In my speech, I will also say ajnfort (Einfort – hall), šlafrok (Schlafrock – bathrobe) and šnala (Schnalle – hairpin), even though I am not of Esseker origin.

Essekerisch or Esseker German was the language of ordinary people and the more educated and wealthier families sneered at such an (linguistically) exotic jewel. The diglossia in question is vividly presented in the personal narrative of Ms. Jolan, eine Essekerin, born in a family of Austrian and Hungarian Jews who were all arrested by the Nazis in 1942 and transferred to the concentration camp in Tenja, from where they were supposed to be deported to Auschwitz. Luckily, however, Ms. Jolan’s friend’s father, a high ranking official back then, helped them escape and avoid the fate of many of their fellow Jewish citizens. That same Ms. Jolan speaks frankly about the multilingualism in her family and the Hochdeutsch (the standard German) her dad insisted on, endorsing a strong language policy against “some street mixture” (alluding to the Esseker German). After all that time and the collective trauma the family was exposed to, the status of German in the family history still occupies a high place. Only a couple of years later, some other Essekers (Volksdeutscher), whose less fortunate relatives will end up in the same camp at Tenja, will shamefully hide their mother tongue, just like their origin, keeping it behind closed doors, revealing it rarely only to a few remaining relatives, not ever to be spoken in front of the children.

In the fifties and the sixties people from all over what was then Yugoslavia poured into Osijek, most of them emigrating from Zagora and Herzegovina, those passive and rocky areas devastated by hunger and war. The migrants were now creating a new city, no longer Essek, but Osijek. This urban centre of the Baranja and Slavonia regions with its fertile lands and pleasant climate and the hard-working people from the south were to form a long-lasting symbiosis; entire new town neighbourhoods rose on the outskirts of the Austro-Hungarian art-nouveau centre. My ancestors came and lived there, first in the Downtown and then in Retfala. But the ikavian dialect and exotic accents soon disappeared, drowned in “brotherhood and unity”, and perhaps even more, in “white racism” (orders of indexicality are neatly fixed, slowly prone to change, and the south is always the Others) and in 1983 when I started first grade in Vladimir Nazor Primary School in Retfala, I could not hear the difference between my teacher’s and my grandmother’s speech.

It’s 2018. I’ve been living in Zagreb for twenty years and I still get asked if I’m from Osijek. The recognizable speech of the city is reflected in its slower cadence, unfamiliar to all other Croatian dialects. This slow speech rhythm, no longer as transparent and neutral to me as it used to be (for years, I have been exposed to my new kajkavian family) makes me want to ask (but I refrain from it) waiters, shop-assistants and numerous others here in Zagreb if they are from Osijek too. The massive emigration trend, particularly to London and Dublin, where numerous people from Osijek are in search for a better life, dominates the news.

Now I worry that this trend might last forever, but, on second thought, the truth is that those who stay have a choice, at least as far as languages and education are concerned. The children of my Osijek friends most often learn English as the first foreign language, as it is an obligatory subject from the first day of primary school. Then come German, Italian or French – optional subjects from the fourth grade of primary school and there are all those minority languages offered through the C model – Hungarian, Slovak, Albanian, and once again, German. Osijek’s Classical Gymnasium, just like a century ago, provides classes of Latin and Greek to the most exquisite Osijek pupils. Some open-minded parents send their children to Hungarian kindergartens, and when I hear their little ones recite or sing nursery rhymes in that physically close, yet so different language, I still feel admiration and hope. Hope for languages, people and the city, the city whose at moments rich historical diversity and acceptance of Others can still serve as a model of inclusiveness that Europe is trying hard to achieve.