25.02.21

اليوم العالمي للغة الأم وعيد ميلاد HLD الخامس

By Dina Mehmedbegovic-Smith and Thomas H Bak

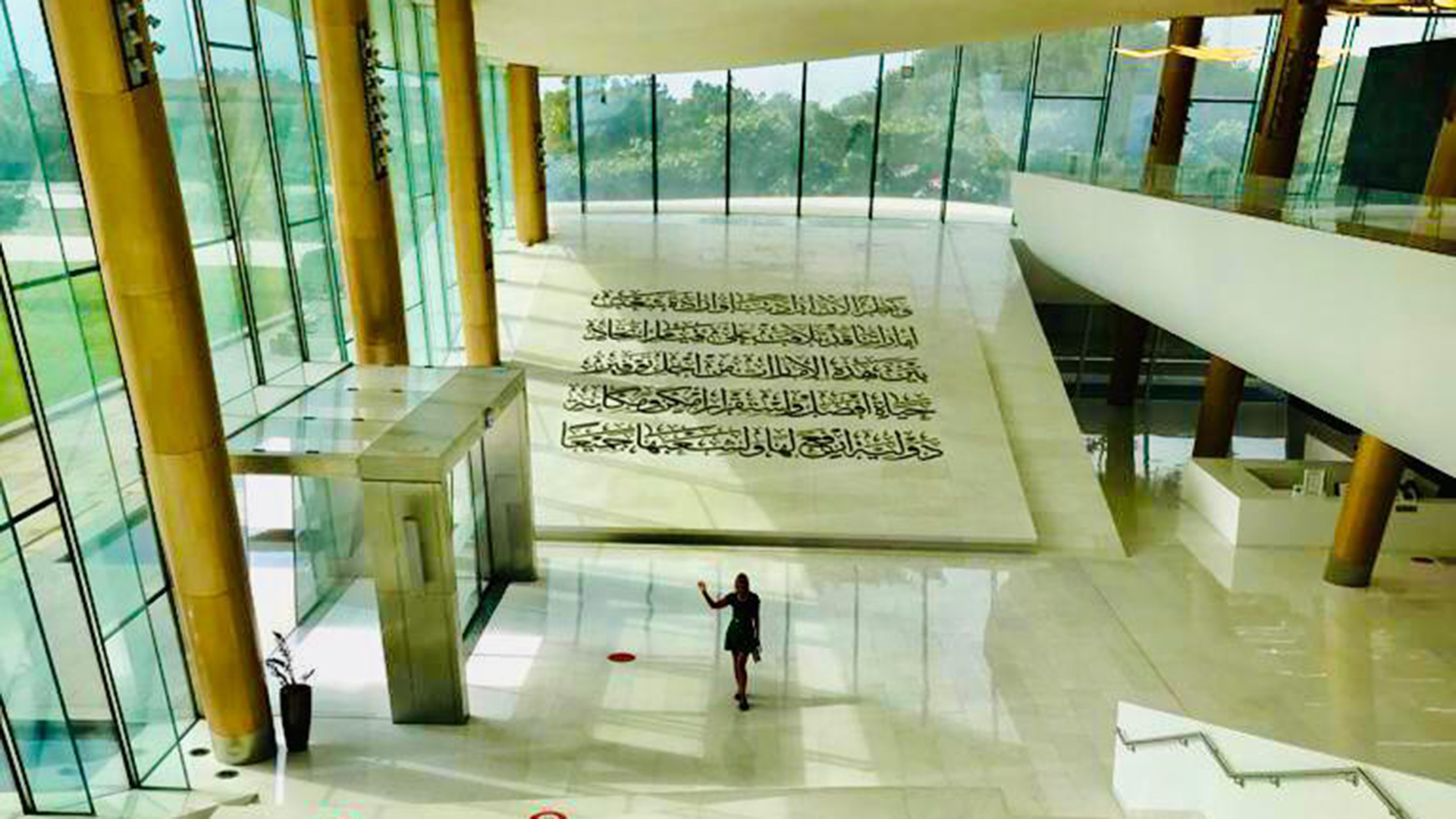

Image top: Monument to the UAE Constitution, Etihad Museum, Dubai

On Sunday 21st Feb we mark the UN International mother tongue day and Healthy Linguistic Diet Website marks its 5th birthday! We are pleased to look through our news section News Archives – Healthy Linguistic Diet, which lists many of our activities and achievements in fulfilling our mission: reaching out to educators, parents, children and policy makers with accessible knowledge on cognitive benefits of bilingualism and our approach to language learning as a part of our life-long wellbeing.

As it is a tradition now we have written joint blogs for this occasion. This year we focus on Arabic.

We wish all our colleagues and everybody marking the UN International Mother Tongue Day every success with their activities. We would love to hear about your initiatives – please get in touch,

Dina and Thomas.

نظرة عميقة في صراعات اللغة العربية كلغة أم

دينا محمدبيقوبش – سميث

هناك العديد من الدول الناطقة بالعربية تكافح أيضًا تهميش اللغة العربية، وبالتالي فإن هذه قضية ذات أهمية في منطقة الخليج ومناطق العالم الأخرى، حيث إن اللغة العربية هي اللغة الأم. ووفقًا لعدد من التقارير البحثية التي ترشد إلى أنه يُنظر للعربية على أنها المادة الأقل إعجابًا للطلاب في المدارس وهي آخر الأشياء التي يريدون القيام بها. رجوعًا للمراجع: (الزيني ، 2016 ؛ العربية للحياة ، 2014 ، طه ، 2019)كشفت الاستشارات التي أجريت مع مواطنة إماراتية أن المتخصصين في مجال التعليم يخشون مستقبل اللغة العربية في الإمارات. وعندما سُئلت عن تصورها لمستقبل اللغة العربية في 20-30 سنة، كان ردها: “لا تجعليني أبكي”. فقد كشف جميع المعلمين الذين استشرتهم بشأن مستقبل اللغة العربية عن قلقهم وخشيتهم عليها حيث إنهم يلاحظون في أسرهم وأقاربهم الذين أصبحوا الآن آباءً صغارًا أنهم يستخدمون اللغة الإنجليزية للحديث مع عائلاتهم، ويخشى الأطفال الإماراتيون الذين تقل أعمارهم عن خمس سنوات الذهاب إلى المدرسة، لأنهم يدركون أنهم لا يستطيعون تحدث اللغة العربية ، فقط ليكتشفوا حقيقة أن ما يبعث على الارتياح الشديد أن الجميع في المدرسة يتحدثون الإنجليزية أيضًا في معظم الأوقات.

وقد قدم أحد معلمي اللغة العربية الذين تمت استشارتهم رؤى ثاقبة حول ملاحظة الآباء من أصول عربية الذين يستخدمون اللغة الإنجليزية مع أطفالهم أثناء الاستمتاع بوقت العائلة. حيث يستخدم هذا المعلم مبادرته الخاصة للتواصل مع أولياء الأمور في مثل هذه المواقف وإرشادهم حول أهمية استخدام اللغة العربية مع أطفالهم. كما أنه عمل على رفع مستوى الوعي بين الطلاب في مدرسته وتشجيعهم على استخدام اللغة العربية في أوقات الاستراحة. وتُظهر هذه الأمثلة – أن الصراع حقيقي في كل حالة من حالات استخدام اللغة العربية في العديد من السياقات، حيث أصبحت اللغة الإنجليزية بصمت اللغة المفضلة.

لماذا يحدث هذا للغة تعد لغة عالمية تحتل المرتبة الخامسة في العالم مع 313 مليون متحدث عالميًا؟

وفقًا لتقرير حديث طه (2019): “يأتي معظم الأطفال إلى المدرسة بعد أن اكتسبوا نوعًا واحدًا أو لهجة من اللهجة العربية ، وهي تلك التي سمعوها في المنزل من الآباء وأفراد الأسرة. في المدرسة ، لغة جميع الكتب المدرسية وأدب الأطفال والتعليم المفترض هي MSA (اللغة العربية الفصحى الحديثة) ، وهي مجموعة موحدة من اللغة العربية المستخدمة في وسائل الإعلام والأدب وجميع وسائل الاتصال الرسمية والمكتوبة. عادة ما يتم تدريس اللغة العربية بطريقة صارمة تركز على القواعد والدقة. وقد أدى ذلك إلى خنق قدرة متعلمي اللغة العربية على استخدامها كأداة للعلم والعمل الإبداعي والمصطلحات الحديثة والأفكار المبتكرة والمرح والاستقصاء والضحك (Taha-Thomure 2008) يتم توجيه الطلبة باستمرار على الفور في الفصول الدراسية ويتم تعليمهم أنه لا يمكن للمرء أن يخطئ عند القراءة أو الكتابة باللغة الفصحى ، وأن التهجئة المبتكرة وصنع الكلمات هي ممارسات غير مقبولة. فالقضايا الرئيسة التي تحتاج إلى معالجة هي: تحديث تدريس اللغة العربية وتعلمها ، والتدريب الأولي للمعلمين ، والتطوير المهني لمعلمي اللغة العربية. فعدد قليل جدًا من المدارس الخاصة ، على سبيل المثال ، تشجع تعلم الموسيقى العربية ، أو استخدام اللغة العربية في النشرات الإخبارية ، أو عروض المواهب ، أو المسرح ، أو الإعلانات ، أو الأعمال الفنية المعروضة. وهذا يحد من وجود اللغة العربية في الفصل الدراسي فقط، وغالبًا ما يرسل رسالة إلى المعلمين وأولياء الأمور والطلاب مفادها أن اللغة العربية ليست لغة مهمة وممتعة.وقد ذلت القيادة الرشيدة في دولة الإمارات العربية المتحدة، ولا سيما الشيخ محمد بن راشد – نائب رئيس دولة الإمارات العربية المتحدة وحاكم دبي – الكثير من الجهود والموارد في تطوير السياسات والمبادرات ودعم وزارة التربية والتعليم في دولة الإمارات العربية المتحدة لتحسين الوضع وتوفير اللغة العربية في نظام التعليم. وقد رحّبت المدارس والمعلمين بنتائج هذه المبادرات. وخلال مشاوراتي مع المعلمين من مختلف الملفات الشخصية ، تم الإقرار بوجود تحسينات واضحة من حيث عدد ساعات توفير اللغة العربية ، والتي هي حاليًا أربعة دروس في الأسبوع في المدارس الدولية والمعايير المطلوبة لتوفير اللغة العربية: لمدرسة يهدف إلى الحصول على حالة ممتازة بشكل عام يجب على الأقل تقييم توفير اللغة العربية على أنه جيد. حاليًا ، هناك مدرسة واحدة فقط في دبي تصنف اللغة العربية التي يحكمّها المفتشون ممتازة.

يعد وجود المدارس والجامعات والخدمات العامة باللغة الأم أمرًا مفروغًا منه في معظم السياقات من قبل معظم سكان العالم. اليوم الدولي للغة الأم هو تذكير مهم بأن لكل دولة تاريخًا في تطوير لغاتها وحقوقها في استخدام لغاتها ، وأن بعض المجتمعات ، حتى تلك التي تُصنف لغتها الأم كلغة عالمية، لا تزال منخرطة في معارك ضد العديد من العوامل العلنية وغير المعلنة التي قد تؤدي إلى فقدان اللغة على المستوى الفردي والموت اللغوي على المستوى الإقليمي / العالمي ، في المستقبل البعيد.

المراجع:

الزيني 2016 محادثة مع أحد أكثر معلمي اللغة العربية تأثيرًا في العالم. تم الاسترجاع من Link

تقرير اللغة العربية مدى الحياة (2014) المكتب التنفيذي لرئيس وزراء دولة الإمارات العربية المتحدة

طه، حسن (2019) تعليم اللغة العربية في الإمارات: اختيار السائقين المناسبين. 10.1007 / 978-981-13-7736-5_5

Insight into struggles of Arabic as the mother tongue in Dubai

Dina Mehmedbegovic-Smith

Central Dubai sunset

In December 2020 my husband and me found ourselves in Dubai with the plan to spend five days in this amazing city. As the news from London got worse day by day during our stay here, we decided to postpone our return flight. Six weeks later, we are still here, UK is in a very strict lockdown, direct flights from Dubai to London have been banned and very expensive compulsory hotel quarantine has been enforced for anybody returning from a whole list of countries, including the UAE. As the situation in London has deteriorated beyond any imagination, I have embraced this opportunity to live and work in this fast growing multilingual multicultural metropolis with some extraordinary qualities.Based on my insights gained in meetings with school leaders, inspectors, teachers, parents and children, while in Dubai, I have quickly realised that there are serious concerns about the provision, positioning and future of Arabic in education and everyday life in the UAE. Although not unique, this is a very unusual situation since Arabic is the official and mother tongue language of the UAE. There are other Arabic speaking countries also battling marginalisation of Arabic and therefore this is an issue of wider importance in the Gulf region and other world regions, where Arabic is the mother tongue. According to a number of research reports: ‘Arabic tends to be seen as the least liked subject for students in schools, and speaking, reading, and writing in MSA (Modern Standard Arabic) are the last things they want to do, and actually are able to do (AlZeny, 2016; Arabic for Life, 2014, Taha, 2019). Consultation held with a school inspector and an Emirati national revealed that professionals in education fear for the future of Arabic in the UAE. When asked how she perceived the future of Arabic in 20-30 years her reply was: “Don’t make me cry.” All the educators I have consulted are very anxious about the future of Arabic in public and private spheres. In their own families they observe their relatives, now young parents, using English in their family time. Emirati children as young as five fear going to school, because they are aware they cannot function in Arabic, only to find out, to their big relief, that in school everybody speaks English too most of the time.

One of the consulted teachers of Arabic provided insights into observing Emirati parents using English with their children while enjoying family time. This teacher has been using his own initiative to approach parents in such situations and advise them about the importance of using Arabic with their children. He has also been raising awareness amongst students in his school and encouraging them to use Arabic during break times. These examples show – that the struggle is real for every instance of using Arabic in many contexts, where English has silently become a language of choice.

Why is this happening to a language which is considered a world language, ranked 5th in the world with 313 millions of speakers globally?

According to a recent report Taha (2019): “Most children come to school having acquired one variety or a dialect of Arabic, and that is the one they have heard at home from parents and family members. At school, the language of all textbooks, children’s literature, and supposedly instruction is MSA (Modern Standard Arabic), which is the standardized variety of Arabic used in media, literature, and all formal and written communication. Arabic language is usually taught in a rigid way that is focused on grammar and accuracy. This has stifled the ability of Arabic language learners to use it as a tool for science, creative work, modern terminologies, innovative ideas, playfulness, inquiry, and laughter (Taha-Thomure, 2008). Students are consistently corrected on the spot in classrooms and are taught that one cannot make a mistake when reading or writing in MSA, and that invented spelling and making words up are unacceptable practices. The main issues which need addressing are: modernising teaching and learning of Arabic, initial teacher training and professional development for teachers of Arabic; very few private schools, for example, encourage learning Arabic music, or the use of Arabic in newsletters, talent shows, theater, announcements, or artwork displayed. This limits the presence of Arabic language to the classroom only and often sends the message to teachers, parents, and students that Arabic is not an important and fun language.”

View from Burj Kalifa

The leadership of the country, especially Shaikh Mohammad Bin Rashed, the vice president of the UAE and ruler of Dubai, has put a lot of effort and resources into developing policy and initiatives and supporting Ministry of Education in the UAE to improve positioning and provision of Arabic in the education system. The results of these initiatives have been welcomed by the schools and educators. In my consultations with educators of different profiles it has been acknowledged that there are visible improvements in terms of numbers of hours for the provision of Arabic, which is currently four lessons a week in international schools and required standards of Arabic provision: for a school that aims to have overall outstanding status, Arabic provision has to be at least evaluated as good. Currently only one school in Dubai has their provision of Arabic judged by the inspectors as outstanding.

Having schools, universities and public services in one’s mother tongue is taken for granted in most contexts by the most of the world populations. International mother tongue day is an important reminder that every nation has a history of developing their languages and rights to use their languages, and that some communities, even those whose mother tongue is classed as a world language, are still engaged into battles against many overt and covert factors which may lead to language loss at the individual level and language death at the regional/global level, in less or more distant future.

References:

AlZeny, I. (2016). A conversation with one of the world’s most influential Arabic teachers. Retrieved from: https://www.alfanarmedia.org/2016/11/conversation-one-worlds-influential-arabicteachers/

Arabic for Life Report (2014) The UAE Prime minister’s Executive Office

Taha, H. (2019) Arabic Language Education in the UAE: Choosing the Right Drivers. 10.1007/978-981-13-7736-5_5.

BlogAll posts

23.02.24

‘Saya merasa kehilangan’:

Apakah hilangnya bahasa ibu di Indonesia masih bisa dicegah?

Gambar di atas: Bersama para wisudawan di Universitas Udayana Translated by: Ince Dian Aprilyani Azir Tanggal More

23.02.24

‘Titiang Kaicalang Kasujatian Ragan Tiang Pedidi’:

Prasidakeh kereredan basa ibu ring Indonesia ketambakin?

Gambar ring baduur: Sareng lulusan Universitas Udayana Translated by: Ni Putu Sri Suci Artini Asih and More

21.02.24

‘I feel a loss in myself’:

Can the loss of mother tongues in Indonesia be prevented?

Image above: With the graduates at University of Udayana On February 21st we mark the UN More

18.12.23

When concepts migrate: Complexities of migrating Healthy Linguistic Diet

Image above left: Thomas giving a keynote at the first International Conference on Language Development and Assessment More